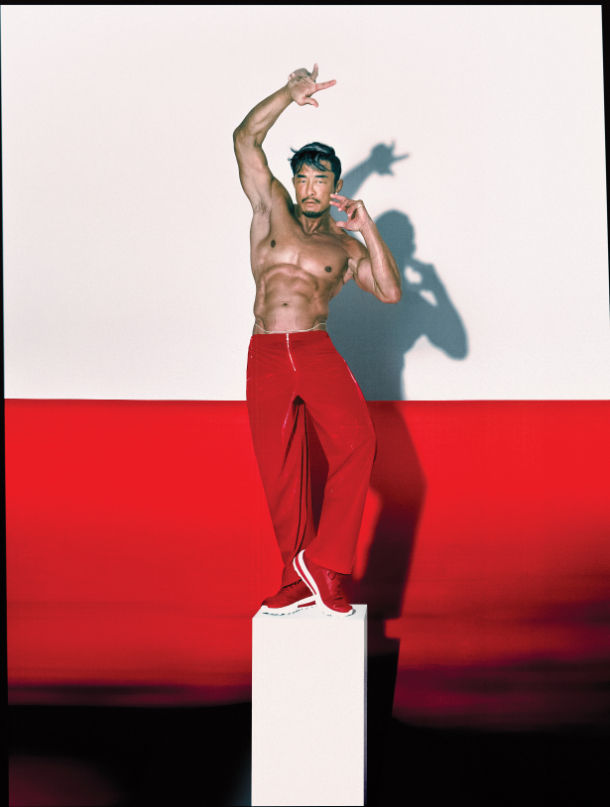

Choo Sung-Hoon’s Long Game

To mixed martial arts fighter Choo Sung-Hoon, age isn’t just a number, it’s a challenge.

Words JOEY WONG

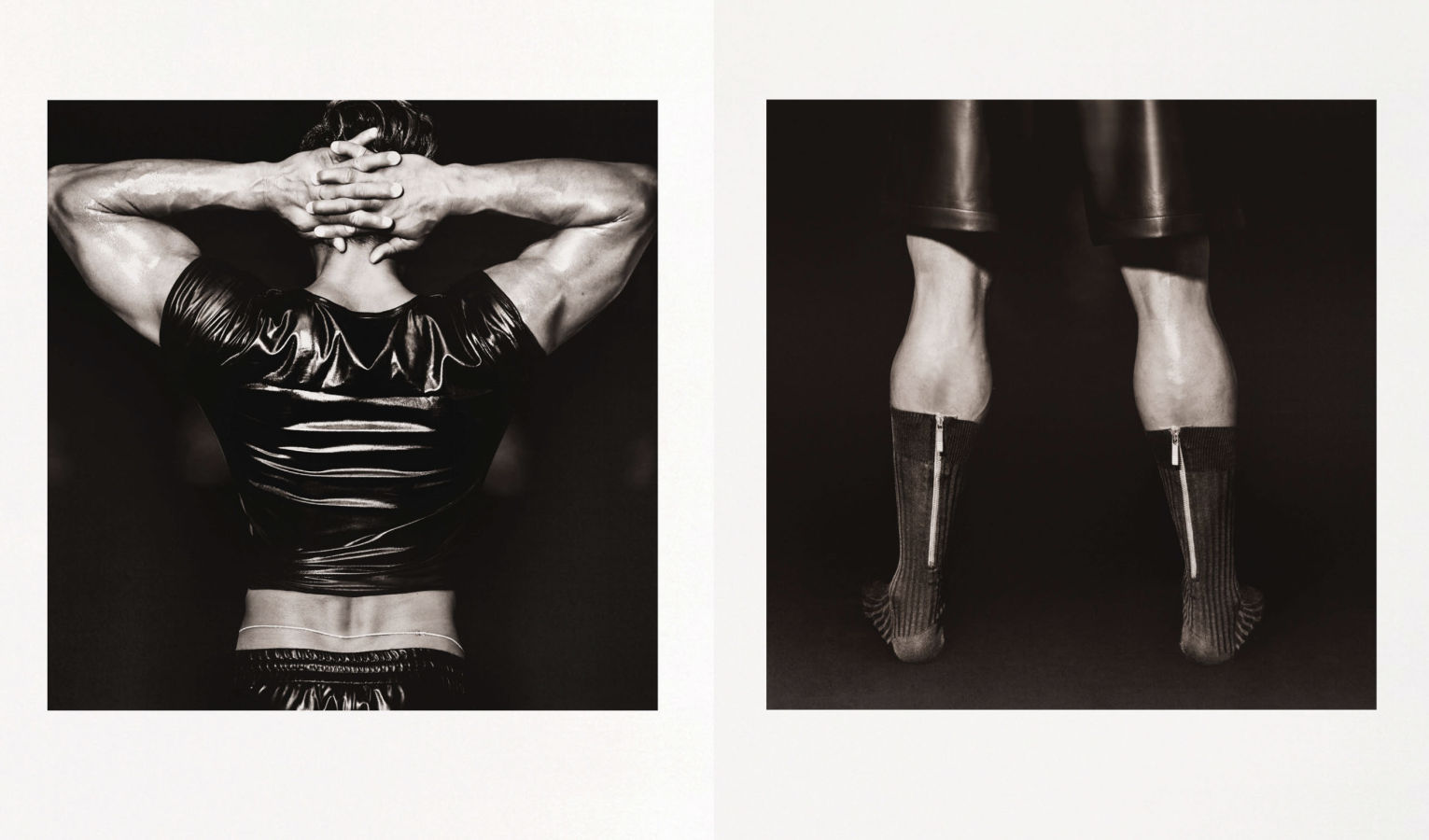

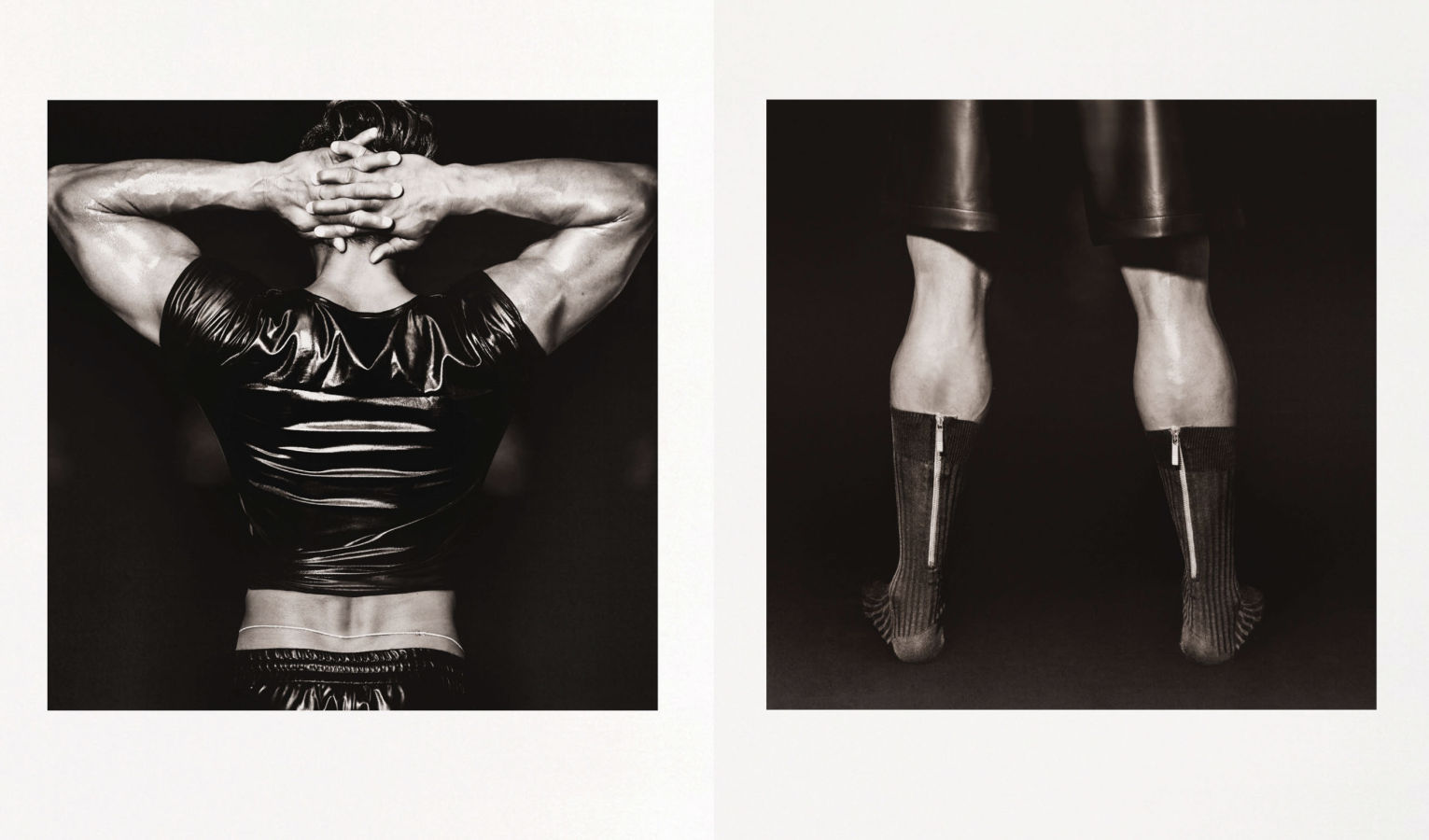

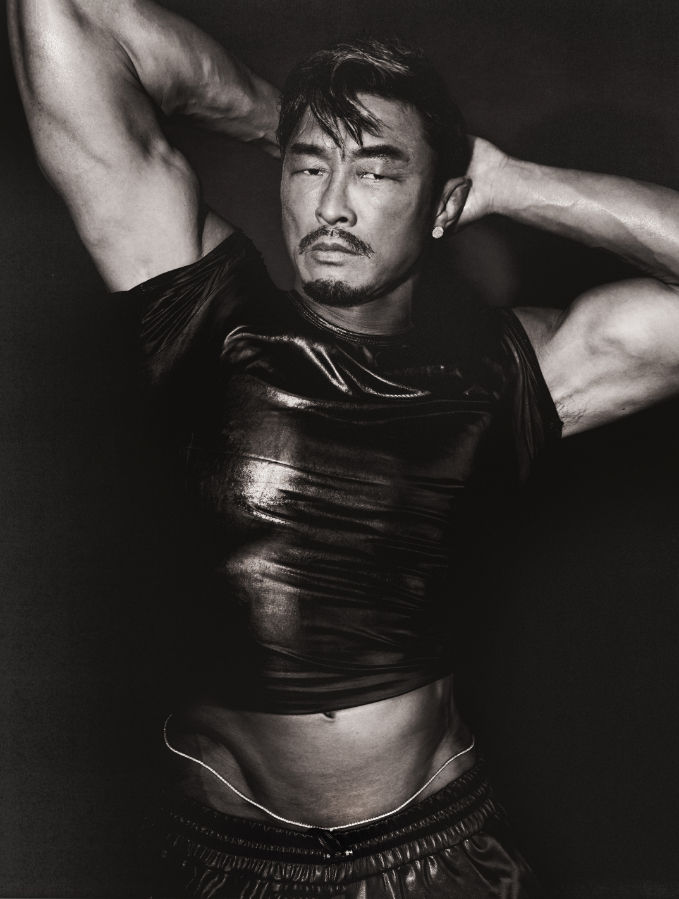

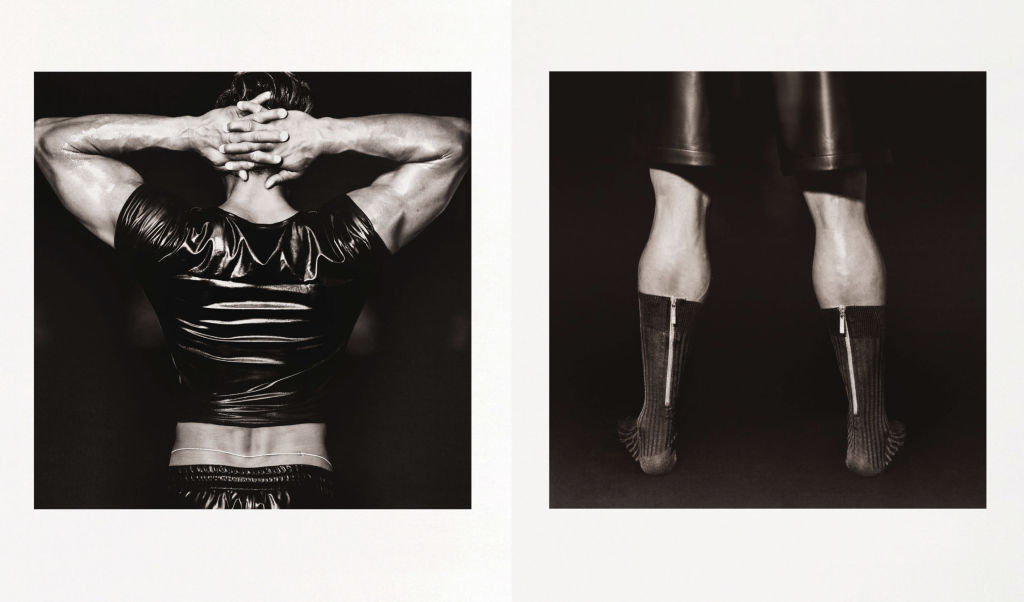

Creative Direction and Styling ALVIN GOH

Photography REUBEN FOONG

Hair SING TAM at Artify Lab

Photography Assistants OSCAR, KING WU

Styling Assistants VICTORIA, HEBE

Legend has it, there once was a king who cheated death. Angry as the gods were – and they were known for their wrath – they bored into him an eternal sentence: to push, with all his might, a boulder up a mountain … only to have said boulder cursed from ever reaching the top. For when it nears the precipice, it’s jinxed to roll backwards down … down … down, back to where it started. Every time this happens, the king is compelled to follow, to return to the foot of the mountain and restart, all over again. And again. And again. And so, the king who cheated death was thus condemned to an afterlife of toiling, laborious effort that leads somewhere. Then, all at once, nowhere.

This was the curse of Sisyphus.

“Whoa.”

“No way.”

“It is him!”

“We’re screwed.”

Appropriately, a cacophony of gasps fills the arena when Choo Sung-Hoon, with his signature bronzed skin, signature pressed suit and signature wayfarer shades, strides on to the set of Netflix’s Physical 100. As excited contestants scurry, one after another, to Choo for handshakes – a “crazy calloused” handshake, so says wrestler Jang Eun-sil – a pecking order is thus established before the competition has even had its first quest: Choo is the one to beat.

It has to be so. Choo, who became a world- champion judoka at age 26; who then retired from competitive judo to compete in mixed martial arts at age 29; who received the nickname “Sexyama” while squaring off in Ultimate Fighting Championship’s octagonal cage; who has since vowed to fight until his 50th birthday, is the show’s most recognisable, most decorated and most venerable athlete. And, at age 47, he’s also the oldest.

When Netflix first contacted me [about Physical 100], I actually declined the offer,” he recalls. He can hold his own against a younger, possibly stronger opponent in speedy five-minute mixed-martial-arts rounds, no problem. But 99? He takes pause. “After some thought, I thought this might be the opportunity of a lifetime. I’m almost 50 now. I realised I wanted the world to see middle-aged people like me win… and know that it’s still possible to win.” So, he said yes. He’ll be there.

Upon reflection, it seems entirely out of character for Choo to have had that wisp of doubt, that errant inkling to refuse a chance to be challenged so. After all, he’s only ever wanted this, to be challenged in the face of arduous physicality. He’s always felt he had to, as “studying was just not for me”, Choo sheepishly admits, hoisting his left arm overhead. “That’s where my grades for phys-ed were. And everything else,” his right palm slices, hovering near his hip, “here.”

Choo, who has fond memories of being shuttled to the dojo since the age of three – his father was a judo instructor – has long seen the sport as something of an education. It’s taught him manners. Taught him respect for his opponent. Taught him discipline. Taught him seiryoku zen’yō – prioritising technique over brute force.

“Because to me, strength means …” Choo starts. He’s trying to come up with the right word, resorting to whipping out his phone for a translation app.

“Kindness,” Siri chirps.

“Yes,” he continues, “kindness.”

“Sportspeople are naturally competitive,” Choo says, “it’s what drives us. For a winner to be crowned, it means there has to be a loser. And in [Physical 100’s] case, there has to be 99 losers.”

Choo’s run on Physical 100 started with a whimper. The preliminary task saw the hundred-strong contestants suspended mid-air, hanging squarely by the strength of their grip. Choo was confident he could make it into the top 10 of his division. To his disappointment, he placed 27 in his cohort of 50.

“I’ll show you this middle-aged man’s strength,” Choo teases, when younger mixed-martial-arts fighter-cum-firefighter Shin Dong-guk chooses him as his challenger for a one-to-one face-off the following quest: the loser will be eliminated. “Don’t you underestimate me.”

“I’ll never get an opportunity like this again,” Shin says, lowering his head. His choice to choose Choo was widely lauded as sportsman-like; he’d wanted to fight the strongest person in the arena, despite all the reasons at present to pick a weaker opponent.

“As a fighter,” Choo admits, humbled, “I was very grateful. I think he chose well.”

The fight begins. The objective is to secure a medicine ball at the end of three minutes. But Shin, who wants to fight Choo on his own merits, proposes mixed-martial-arts rules. Choo accepts.

With every jab, every dodge, every flesh-on-flesh impact that sounds like it hurt, it’s patently obvious: Choo has met his match. But, in the nick of time, the 47-year-old exits mixed-martial-arts stance and dives, landing torso-first atop the very object they’re meant to be tussling over. Choo wins. Shin, despite having lost, does nothing but grin. “It was such an honour.”

Choo, who proceeds, goes on to win across the board for his next two group challenges where he is, naturally, appointed leader.

“Pulling the ship was my most memorable,” he remembers of the two-tonne task. “It was much heavier than we anticipated and it required a lot of teamwork. It’s the type of task that necessitated much more than strength and raw power. There was a lot of strategy involved. We were separated into three teams and we weren’t able to see how the other teams got on. We were just led to the scene of the quest and presented with the task … ‘Ta-da!’”

Indeed, Choo, who mostly fights in the slighter Welterweight division, has never had the density of pure brawn on his side. And when the motions of the quest he’s next slated to enter, named the Punishment of Sisyphus, is revealed, Choo is nervous.

“When I entered the arena, the slope was steeper than I’d thought,” he says. “Just climbing there was already hard, so how was I going to do this with a 100-kilogram rock?”

He goes slowly. Steadily. He pushes the boulder, the height of his hip, with both hands, in the rhythm of his steps. The boulder then falls, with gravity, down the other side of the makeshift slope. He trots down, turns, shakes out his arms and readies himself for a second uphill thrust. He pants. His shirt comes off. Then a third thrust. A fourth.

Imperceptibly, Choo loses pace against the remaining two challengers.

“The last bit at the top, that’s the hardest part,” he says. “That’s when you’re out of energy.”

Against chants of “Sexyama, you’ve got this!” and “You’re doing good,” Choo sweats and rams and just makes it past the precipice– but it’s too late.

“It’s such a shame, yeah. But my stamina and energy dropped and I couldn’t push anymore. But everyone who lost were so encouraging, some even stayed behind to cheer on others that hadn’t yet been eliminated … I think that was what touched me the most,” he says.

This preternatural display of exemplary sportsmanship, though, isn’t to say losing is easy. It almost never is. “I wanted to win,” Choo says plainly. He’d have given the 300-million-won cash prize to his mother. “Success only comes with failure and with every success, failure will follow. So, I don’t think failure is something to be upset over.

“But, of course, failing in competition is devastating,” he reiterates. “Of course it is. And of course I’d want a rematch, always, in an ideal world. But I have no regrets. If I didn’t try my absolute hardest, then I’d be feeling guilty and upset right about now. But that wasn’t the case [with Physical 100].”

And so, a loss. A Sisyphean destiny come true. It doesn’t matter so much, though, as Choo still manages to accomplish exactly what he set out to do: to inspire someone, somewhere, be it a fellow middle-aged man who’s an encouraging word away from trying something new, something challenging. Or a younger person who wanted to witness an unrelenting display of pure tenacity. “If I can do it, anyone can,” Choo says, again and again; it might as well be tattooed across his chest.

The one person he hasn’t managed to inspire? “My daughter is really not a competitive person,” he says, his face lighting up with any mention of his almost-teenaged offspring Choo Sarang. “Maybe it has something to do with having a mixed-martial-arts fighter dad and a mother who’s a model – which in itself is also quite competitive – but she has no interest. I’ve asked her if she wanted to try sports before, definitely. But she’s not into anything competitive. So, she’s probably not going to go into my line of work.

“My family actually didn’t watch the show,” Choo reveals. “Sarang refuses to, even though she loves Netflix. My wife hasn’t seen it either.”

These days, Choo finds himself at the foot of several new Sisyphean mountains. He’s busy dipping toes into fashion and design with his athleisure brand SUNG 1975. He’s also busy with something he’s admittedly not so great at. “Golf,” he says, adamantly refusing to comment on his current handicap, “is extremely difficult. That’s why I love it. I can’t love anything easy. It’s just my personality. Golf is difficult, so I want to keep challenging myself and conquer it.”

It’s a hobby-turned-passion Choo discovered seven or eight years ago. “But I play it so sporadically I haven’t improved much since,” he self-deprecates. “I’d probably have been a better golf player than I am now if I’d started earlier, but I only got into playing after the age of 40 because it’s such an expensive sport.” He counts on his fingers. The clubs, expensive. The courses, expensive. The coaches, expensive. “Everything about golf is hard,” he goes on. “You need a high level of concentration, but at the same time, you have to relax. You need to find this right balance between concentrating and relaxing. And the game takes such a long time. Fighting, a match might be five, 10 minutes, so you only have to tune your attention for that amount of time. But with golf, it’s completely different – it’s an entire day of concentrating. But that’s why it’s challenging – and why it’s so fun.”

Choo, who schemes in decades, has a goal in mind. Well, of course he does. “When I retire from mixed martial arts,” he says, “I want to play golf every day until I’m 70. And when I’m 70, I want to play Tiger Woods.”

He beams big as he voices this pipe-dream of an ambition – “I’m the same age as Woods!” – and yet, even in jest, it doesn’t feel at all improbable that this might be an entirely possible future. Because if there’s anyone that’d make a playoff with Tiger Woods happen, it’d probably be Choo – he’d have practiced enough times to accept the challenge by then – and it’d probably be exactly on schedule, too.

Because to Choo, he’s a walking billboard of achievable dreams.

Even the Richard Mille watch that adorns his wrist, the jingle-jangle of diamond-encrusted bling that encircles his other, he explains, are lessons in grit. He’s once yearned for such luxuries, flipped through the glossy magazines and dreamed. So, he’s gone and done it, earned it. And, therefore, so can you. (Choo, who’s a bit of a magpie for watches, admits to selling a timepiece with every loss. Physical 100 cost him, painfully, a Patek Phillipe.)

For every morning he wakes before he really wants to squeeze in a 45-minute bodyweight workout; for every MMA fight that’s taken him away from his family; for every lesson his late father taught him, in judo and in life, that he still holds near and dear … every sacrifice he’s ever made is a boulder, heavy in his palms. And every success, as far as he’s concerned, is just the same boulder half-shoved up a never-ending mountain. “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart,” surmises philosopher Albert Camus. “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

And Choo, easy with a grin, is patently so. On to the next.