Yusaku Maezawa on His Space/Art Odyssey

The universe – and how art might save it – according to one remarkable Japanese billionaire, Yusaku Maezawa.

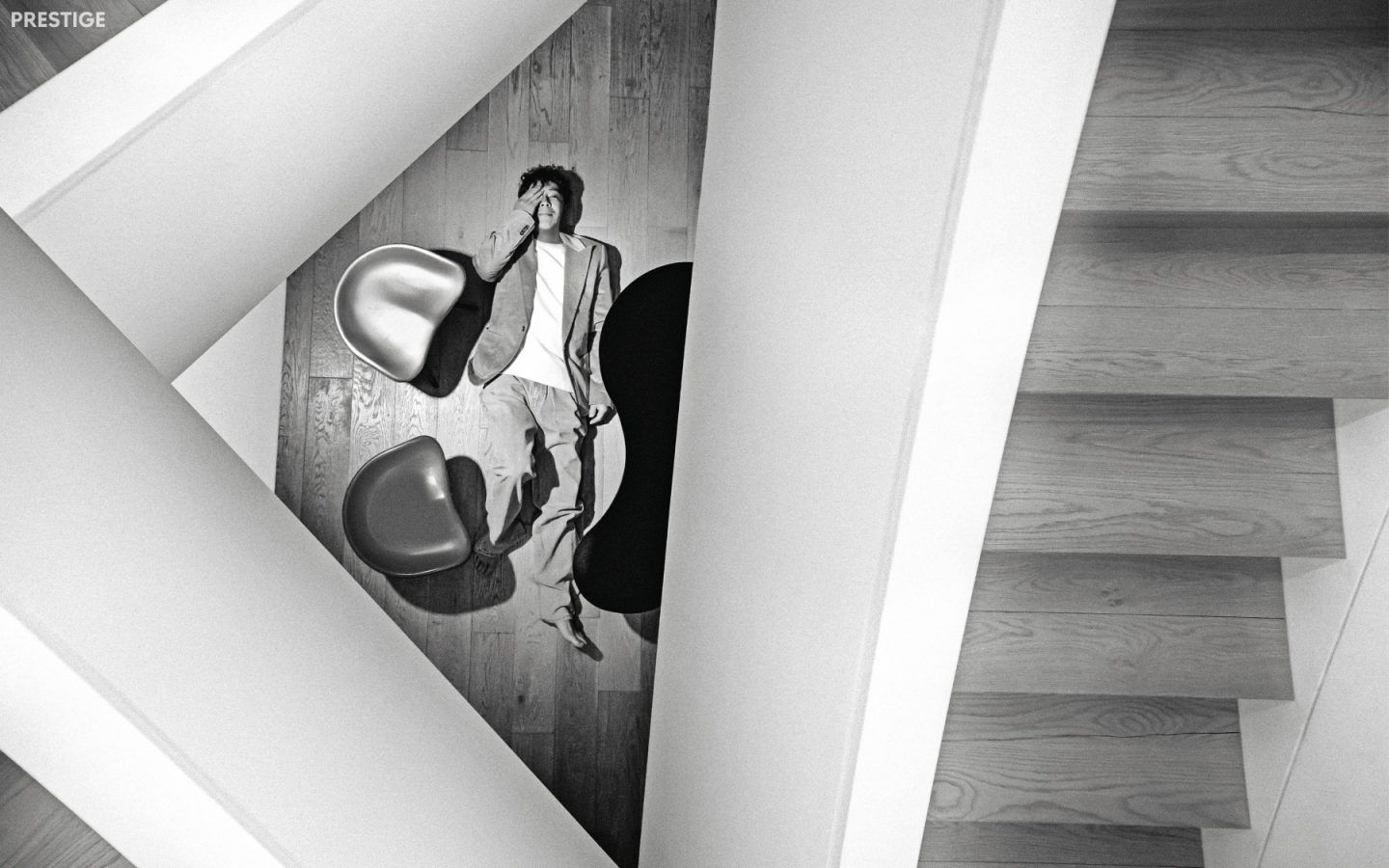

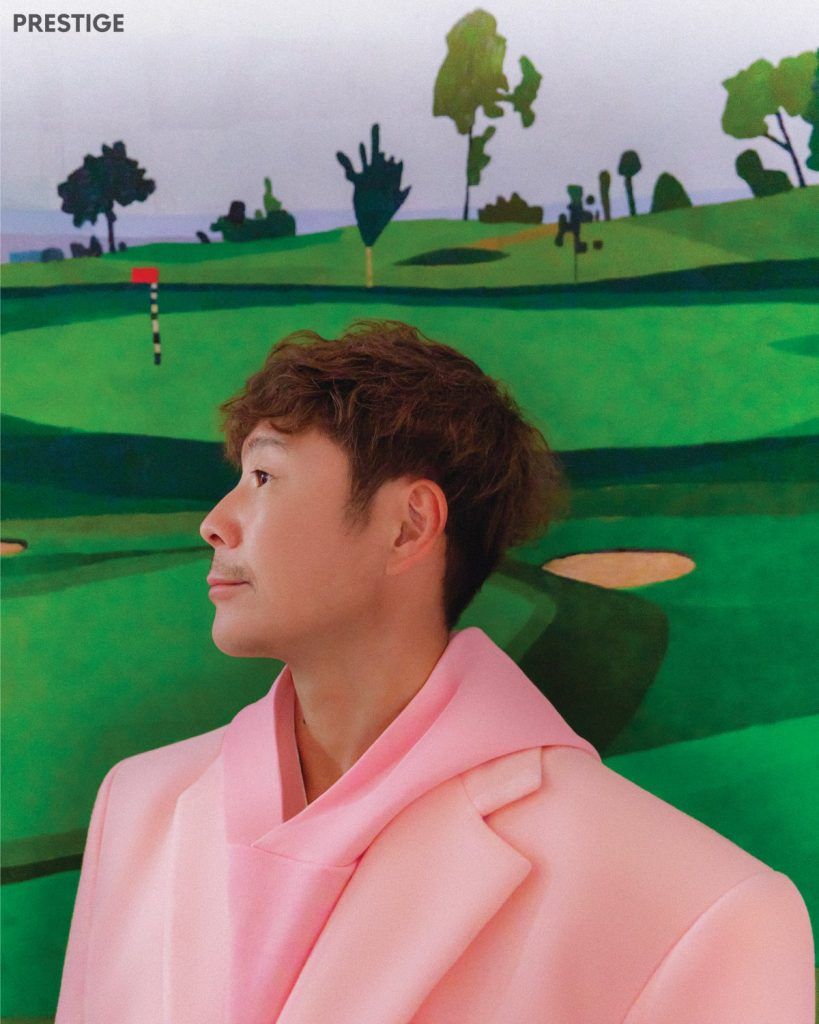

We pinch ourselves as we walk into the home of Japanese art collector, Space adventurer, entrepreneur and philanthropist extraordinaire, Yusaku Maezawa, the man whose exploits blazed in klieg lights for the majority of 2022.

After all, when wasn’t he headlining our news cycles? Halfway through the year, he sold a Basquiat at Phillips auction house in New York, on the premise that more people would be able to see it, and by December, was announcing on his digital platform, dearMoon, the crew he’d finalised for his week-long flyby of the Moon this year on Elon Musk’s inaugural SpaceX Starship rocket. But this isn’t just some joy-riding, showboating space jolly, whereby Maezawa’s riding on the coattails of his 12-day stay on the International Space Station in 2021. This is a “space art” voyage. Consider it like a supreme expression and manifestation of Japan’s hugely experimental Gutai art movement, as Maezawa and his self-curated crew of eight photographers, artists and filmmakers will make their liberated way into the galaxy and attempt to make art within the relative constraints of space travel. “It’s an exciting ride,” he says. “We have no idea what will happen. It’s like a journey into the unknown.” But right at this moment, honoured and humbled guests that we are, Space can wait.

There’s a festoonation of art to marvel at from the get-go. Almost immediately we pass a Duane Hanson Security Guard (1990) just inside the door, the hyper-realistic sculpture catching us by surprise, as they always do, in that “is-he-or-isn’t-he-alive” state. Maezawa grins. The veracity of Hanson’s work often provokes interaction with living people and his work anticipated the likes of Italian impresario Maurizio Cattelan. Going downstairs, we find above us, suspended from the ceiling, an Alexander Calder – Mobile suspendu avec deux croissants (1940) – in painted metal and steel wire. Calder always carried wire and pliers with him so that he could “sketch” as he moved around, a technique that became known as “drawing in space” – which seems an apt description given Maezawa’s pending art mission on the SpaceX Starship. Before we’re even seated, both pieces have alerted us to the playful yet perspicacious nature of Maezawa’s collecting habits.

Casually accoutred in a hoodie and shorts, Maezawa beckons us to take a seat, but in his world that means not just any seat. We settle in a distinctive playful red couch that turns out to be by French interior designer Jean Royère and was first called the Ours Polaire (polar bear) sofa when designed in 1947. Maezawa, it transpires, is as committed to collecting furniture and design pieces as he is to more traditional art, and he later shows us a series of Jean Prouvé chairs, the earliest the Cité (1938), a bookcase by Charlotte Perriand (1958), floor lamps by Jean Royère and a pair of Diego Giacometti low tables from the 1940s. Not everything is a “work” though. While the expansive and tall white rooms have the feel of a gallery space, there are bookshelves with myriad titles, mostly art- or design-related, and model aircrafts, vases and pots, and an impressive array of crystals standing like stalagmites. There are also quirky curios, such as personal message cards with drawings from Jonas Wood and various photographs of his other-worldly life spent aboard the ISS.

But the longer we gaze and appraise, the more it’s nigh on impossible not to be distracted by the gilt-edged array of premium (and unlikely) pieces on show in the two floors of the house that we walk through. There’s a gritty, fabulous – and early – Bruce Nauman neon (1941); On Kawara’s quietly declarative Nov 22, 1975, which is Maezawa’s birthday – in fact there’s so much On Kawara the house feels like something of a mini-shrine to the artist; Ed Ruscha’s simple, conceptual, Dada- influenced Peach (1964), and Lace Leaves (2022) by newly covetable Polish artist Ewa Juszkiewicz (represented by Gagosian and Almine Rech, followed by Cindy Sherman, and tipped as one of three female artists to watch by Katy Hessel in last year’s best-seller, The Story of Art Without Men). Maezawa recently shared the work on his Instagram.

OK. Confession time. We went into this rare meeting with the former online fashion retail tycoon thinking in matters of art we’d mostly be discussing: his predilection for Jean-Michel Basquiat and how, in 2017, he set the art world a-twitter with his US$110.5 million purchase of the artist’s blue-infused Untitled at auction in New York. And how, just last year, he sold another Basquiat Untitled, which he’d bought in 2016 amid a surge in the artist’s prices. How wrong we were. In reality, there’s way more to Maezawa than meets the eye in just about everything his interests cover – and that’s one cosmically wide expanse of commitment. He collects and encourages emerging and established artists across the board, it transpires, and even took a work by one, Ida Yukimasa’s L’Atelier du peintre, to the ISS, “like a bunch of flowers to brighten up the very bland and very austere nature of the interior”. But before we broaden our discussion, he stops to highlight his affinity for Basquiat and that work: the blue one.

Maezawa was a drummer in a Japanese hardcore punk band, while a decade or so earlier, Basquiat had played for a New York punk-rock band called Gray. “Basquiat is not only an artist or just a painter, but also a musician. And I always found his passion very cool. So I found him to be a well-rounded artist. And I like his lifestyle,” Maezawa tells us. But not all of it. “That’s not to say I like every single piece of his work. There are works he’s done that I don’t feel really attracted to at all, and which I think are not great,” he declares. We suggest to him, somewhat sheepishly, that a little bird had told us he’d cried upon first seeing the “blue Basquiat”. Was that so? The room holds its breath; the only thing that moves is the Calder above us. He pauses at the recognition, which, given his expression, still appears to resonate. “I was really touched and overwhelmed by the experience of being there in person, and just had this amazing feeling of a kind of personal connection. It just seemed to shine. But not only is the work and its aura so very powerful; I also thought it a little bit sad and even transient as well.” Moment. Outside of that, Maezawa explains that separate artworks spark distinct feelings in him. “Generally, I invest in art which I have strong feelings towards, but there are always different reasons each time for why I might buy. Sometimes an artwork is just powerful, like Ed Ruscha’s. It has not any sadness to it.” We concur. It’s feel-good-factor work of high order.

And then we make a silver bullet of a discovery about his first-ever art purchase, a highly stylised Roy Lichtenstein portrait of an overpoweringly beautiful blonde with headband (think Marilyn-ism) in bold outlines with Ben-Day dots mimicking a newspaper or comic. It’s top-tier Ultra Pop and shot through with visual seduction. “At that time,” Maezawa explains, “I used to like Pop Art but only had posters. And this was the first painting that I decided to buy; it’s quite a big piece. A dealer in Japan reached out to me and asked if I was interested. It cost just over US$1 million, which was a big purchase for me, and it was also a bold decision to buy an American work.” A wide, satisfied smile illuminates his face. “From then on, there’s been no stopping me. I can’t stop.”

“The first painting I decided to buy; it’s quite a big piece… it’s also a bold decision to buy an American work. From then on, there’s been no stopping me”

Yusaku Maezawa

And with that, we fasten our seatbelts for Maezawa’s ride, or rides – because why do it once when your aspiration demands more? – into Space. And, once again, his methods surprise. For a man who inhabits the HyNW (hyper-net-worth) elite, his modus operandi is welcoming and engaging, yet also the result of some serious grunt work on his part. Witness his trip to the International Space Station in December 2021, and the training he underwent, which necessitated time in America, Russia, Germany and Japan. It’s all viewable on digital because Maezawa made it so, none of which was a shoe-in given he needed clearance from separate international space agencies and their galactic loads of bureaucracy – in matters of protocol, legality and security – in discerning what he was able to post and show and share and how. “When you’re on the ISS, when you go to different sections, we do need approval and each section has its own manners and rules, and you need to comply with them,” he says. “So in order to be able to enter different sections, you have to get approval from different space agencies,” he explains. “So I went to NASA, ESA and JAXA – at least I didn’t need my passport to travel through different sections in the ISS,” he says with a grin.

He becomes especially animated and enthused when recollecting ISSisms. “The first and second day are always tricky because you get Space sick, quite dizzy and queasy. And everyone gets sick; civilians and astronauts alike. You can replicate the experience by sitting in a chair on Earth and turning it around fast for about 10 minutes. And whether you move from side to side or lurch forward, you still feel sicker. There’s no way to alleviate the feeling. One month before we went to Space they would make us do that every single day in the morning. So, the feeling I had on the Space chair on Earth was pretty much exactly what I felt when I was in Space.” Mercifully he didn’t throw up. “But there’s a vacuum you can use when you’re up there, if you need to. And lots of medication. But after two days, you get used to it.”

And different challenges arose. “I couldn’t really sleep. It wasn’t like you wake up thinking ‘good morning’.” He explains that the sun rises and sets 16 times a day on ISS as it orbits Earth. “The sleeping bag was too warm, but not using one meant floating around the cabin and bumping into things. And there’s noise constantly while you’re up there; with maximum ventilation and air-conditioning and the hum of all the computers on the ISS.” And the return wasn’t any easier. “When I got back to Earth, I kept dropping lots of different things: my smartphone, my toothbrush. And at first, I couldn’t walk because my body felt so heavy. And I would feel sick again. And my brain felt heavy after floating for 12 days. So I went to Space and I came back loving Earth even more. And, honestly speaking, being in Space is not all that comfortable.”

“When I got back to Earth, I kept dropping lots of different things, my smartphone, my toothbrush. And at first I couldn’t walk because my body felt so heavy”

Yusaku Maezawa

As a result of Maezawa’s tireless endeavours, he’s documented the most complete existing archive available of such an undertaking. And as much as it’s an experience to follow his private mission to become “space-ready”, it’s also an education in contemporary space tourism and the rigours of travelling to such an environment, which while not exactly hostile is hardly the most welcoming. Maezawa even spread and shared the cosmic love with aspiring young wannabe space travellers by reaching out digitally and asking followers to assign him 100 tasks to achieve on ISS, which ranged from washing his hair to shaving. Maezawa, a man with a seeming Midas touch for intuiting consumer and cultural vibes, has become the cosmos’s content creator and educator par excellence. Having noticed he’s got a Joseph Albers Homage to the Square [Solemn] on the wall behind us – oh, and was that Chameleon beyond the Hanson a Christopher Wool [it was, and is, from 1990]? – and before we get to some questions concerning his SpaceX art voyage and relationship with Elon Musk, there’s another matter to discuss first. About money. And certain people’s lack of it. And how it’s a corrupting force “polluting people’s souls”. Because this man who’s partial to blue Basquiats is also a humanitarian and philanthropist. So before we get ideas above, ahem, our international space station, and talk Musk and humans as a multi-planetary species, we ask him about his pilot scheme for basic income in Japan, which we’ve heard about. Almost subliminally, Calder’s croissants seem to shift in recognition.

It’s like a social experiment. Maezawa sees basic income – a system that allows citizens to receive money unconditionally on a regular basis – as a key to greater happiness and one that can empower people to make better and more inspired choices than are currently available to them. He enlisted a small team of professors from leading universities in Tokyo to monitor the Basic Income Social Experiment. One thousand individuals in Japan have each received one million Japanese Yen, and the team will study how a life with Basic Income affects them over the course of a year. Moreover, he’s often given away money on his Twitter account – he has the highest following (10 million and counting) of any Twitter user in Japan – to followers in Japan.

People can be happier if they receive Basic Income,” says Maezawa. “If people were given money needed for an adequate living, wouldn’t they have the freedom to enjoy work, [which would] therefore increase people’s labour productivity?” Furthermore, he likens the one-million-yen to a depiction of chance. That is, a chance for people to challenge themselves. “Wouldn’t this change people’s lives for the better?” he proclaims. “Of course, this is just an idea of mine, but why think when you can act? And I hope this social experiment will guide us to a better future.”

In espousing such a plan, Maezawa follows in the footsteps of leading philosophers, from Thomas More and Bertrand Russell to Thomas Paine and John Stuart Mill, all of whom believed a form of basic income might alleviate poverty. More thought it would discourage theft, while Mill believed that money should be given to all, irrespective of their capability to work or not; the American economist Milton Friedman championed the idea, as did US President Richard Nixon in the ’60s. Today, governments in Canada, Finland, the Netherlands, Italy and the UK – and even the folk in Silicon Valley – appear poised to institute some form of Universal Basic Income. The subject has become newly popular in advanced economies such as Japan, with concerns about stagnant trade flows, growing economic inequality, slow productivity gains and, pertinently, automation-driven job losses. One curious aspect of the Maezawa phenomenon in Japan is that some regard him as a self-promoting, self-interested svengali, whose ambitions go little beyond himself. Yet, his latest venture with Elon Musk’s SpaceX Starship, which Maezawa has christened “dearMoon”– and much of what we were party to – suggests the opposite. When Maezawa bought his way on to Musk’s inaugural Starship lunar flyby idea in 2018, he commandeered the entire vessel. Already foreseeing a grandiose art project, he then extended an invitation across the globe asking would-be voyagers to submit short videos and films of their most envelope-pushing and boundary-breaking ideas, as to how they might create art in space, were they to be accepted as crew on the trip.

The response was overwhelming. More than one million people from 249 countries and regions applied, and he and a team of judges assessed the aesthetic credentials of each, over a 20-month period, before announcing the crew last December. Maezawa will thus fund (as yet no date for the trip has been set, though it’s been provisionally pencilled in for 2023) a coterie of artists, photographers, videographers and filmmakers to accompany him, along with DJ Steve Aoki, brother of model and actress Devon, and his best pal, BIGBANG member and art collector, TOP. Despite the latter’s close friendship with Maezawa, TOP still had to apply the same way everyone else did – online and via forms.

One of the projects Maezawa singles out for artistic potential is 38-year-old Irish photographic artist and writer Rhiannon Adam. “She’s a photographer, but she uses Polaroids and one of her ideas is to use this very low-tech technology to capture Space.” Maezawa explains that the majority of photographs taken in space are super high-res using cutting-edge, state-of-the-art technologies. “But her idea is one you probably would never expect to have, in which she will just use the ‘natural’ light.” As for K-Pop king extraordinaire T.O.P, the singer is working on music themed around the Moon, which he tantalisingly promotes on his Instagram, but with no sound.

Remarkably, Maezawa didn’t approach SpaceX; rather, they came to him. “You know, the space community is a lot like the art community; both pretty small, everybody knows each other and word travels fast,” Maezawa tells us. Hence why SpaceX was on to him like a, ahem … moonshot. And with good reason. “So, SpaceX contacted me and made a proposal. We met and they took me to their factory in Hawthorne, LA. I also watched the launch of the first flight of Falcon Heavy at Cape Canaveral. And we gradually built a relationship based on trust. And that’s why we decided to sign the contract. There’s a lot of trust.”

With good reason. To the “non-thrillionaire” or layperson, most striking about Maezawa’s recollection is just how “prototype” the proposition he signed on to with SpaceX was. “Back then, there wasn’t really any kind of seating capacity decided, and they hadn’t really decided how to sell the seats either, so they didn’t have a price chart saying what it would cost,” he says. “I just told him that I was thinking of going with a couple of people and then he came back to us and said, ‘What about 10 to 15 people?’”

How to catch a star? Chiba-born Maezawa, like most children, was fascinated by stars and recalls “seeing Halley’s Comet when I was around 10. You could see it from Earth and I remember watching and thinking how nice it would be to go to Space but, of course, that seemed more like a dream. Now, times have changed and we can go. But I wasn’t one of those kids who wanted to be an astronaut. I was just very curious about Space.”

And what was his first impression of Musk? “Frankenstein,” he says, smiling, by which we assume he means the doctor rather than his iconoclastic alter ego. “With him being an engineer, I’d imagined he’d be very quiet and sensitive, and on the whole he was. Even though we had drinks, the entire time he was more on the quiet side. I think that’s also because he’s got so many other things on his mind all the time.”

Much like Maezawa. It’s clear from spending time with Maezawa that his commitment to art and its practitioners – especially Japanese – is total. And as the founder of the Contemporary Art Foundation, which stages two annual exhibitions annually, and both its annual CAF Awards, given to students since 2014, and the CAFAA Award residency programme for mid-career artists that began in 2015, he’s discovered young artists such as Kota Hirakawa, Sakae Ozawa, Yukimasa Ida, Etsu Egami, Akio Onishi and Kota Arai. He’s also been planning to build a private museum in his hometown of Chiba, just outside Tokyo, which is currently still a work in progress.

Meanwhile, he says the Starship voyage into Space may be his second and last. Now he wants to head South, specifically the Mariana Trench, the deepest place on Earth, one that fewer humans have visited than Space. And probably less physically arduous than blasting towards the heavens. He only sees one catch, pun intended, “With the deep, there’s the problem that you can’t really see much there, but I thought, you know, since I can go there, why not?” However, one motivating factor, as against Space, “is the greater chance of discovering a new life form

in the ocean, which can then be named after its discoverer”. There’s also the practical reality that with the “retirement” of the ISS this decade, fewer civilians or private astronauts will have the chance to stay in Space, with low-Earth orbit flights and lunar flybys taking precedence.

Surprising to the last, Maezawa then delivers something of an epiphany. “Well, I’ve gone to Space and I’m going to the deep sea. So, outside of myself, there’s not much else to see.” He pauses. “So, the next journey will be to look inside myself. I turn 50 soon, and after that I’d be looking at myself more internally. That makes sense. It makes a lot of sense.” He lets the thought breathe. “I’m going to start pottery. I’m seeking spiritual enlightenment, so I want to actually pour my soul into the soil.”

There speaks a pioneer, discoverer and visionary, who’s looked down upon Earth from on high while docking with the ISS, and seen the fleeting wonder of our existence. “When you look at Earth, it looks relatively small and covered only by a thin layer of atmosphere. It’s fragile.” Hence why he feels the need to pour his soul back into the soil and replenish our greatest work of art. In doing such, is he a beacon of hope for not just our planet, but our youth as well? He’s not presumptuous enough – and indeed he’s too modest – to assume as much, but proffers the following: “For the longest time, I’ve been trying to get my message out there that dreams can come true, and I hope that feeling can resonate with some people.” Has being in Space changed his view of art? “One is purchasing an experience, the other is about ownership. But, in either case, both are very impressive and emotional, and have contributed to my personal growth.” Which is still ongoing.

“For the longest time, I’ve been trying to get my message out there that dreams can come true, and I hope that feeling can resonate with some people”

Yusaku Maezawa

In the big picture of the world there are still many things we don’t understand – and one we understand least about is ourselves. For Maezawa, it’s time to discover the space inside our heads, the space of our thoughts, and expedite the potential that courses through the infinite portals of our minds. Soil, clay, pottery, spirit, soul. Art happens, a Calder sways overhead, our universe calls.

Words STEPHEN SHORT

Creative Direction and Styling ALVIN GOH

Photography REUBEN FOONG

Grooming CHIHARU YADA