Why Scent is Such an Evocative, Artistic Medium

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see,” said the Impressionist artist Edgar Degas. These perfumes and perfumeries would like to disagree on the “seeing” part.

Freedom. Fantasy. Fetish. The highfalutin syntax pebbled through zealous marketing copy for the fragrance genus often reads like truly appalling poetry. But, then again, in the same vein of quandary as being tasked to use words to describe colour, how does one accurately put scent into locution, when the olfactive journeys thus undertaken can be so immeasurably varied? Perhaps this is, precisely, why accuracy is reserved for mathematics and the sciences and not the arts.

Because the synapses in our brain-matter may very well strike upon being confronted with a single spritz of jasmine absolute. Or bergamot harvested from Sicily. Or ylang-ylang, base-noted with accords of leather. And while a palette of eyeshadow or a simple brushed-tip eyeliner may have much easier affiliations to art, or the medium that facilitates the art-making, it’s the evocative journeys prompted by scent – be they an icy plunge through suddenly unearthed childhood memories or, simply, “God, that smells awful” – that precisely do as art does: imply, suggest and, for some olfactive blends more than others, for some noses more than others, force a reckoning.

For some, art is so entirely integral to the process of creation it’s a facet entirely woven into the business itself. After all, you’d only have to exit through the Louvre’s gift-shop to wander past a series of Officine Universelle Buly perfumes scented in the image of the priceless masterpieces you can only dream of bringing home – with the fragrances, you can.

“Guerlain and art,” says Ann-Caroline Prazan, director of art, culture and heritage, “have enjoyed a unique, almost unbreakable relationship.” It was recorded that as early as 1828, Pierre-François Pascal Guerlain has associated himself and his brand with painters like Louise Abbéma, who was entrusted to decorate the boutiques. Later, Jacques Guerlain, a steadfast patron of the arts, especially those of Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet – Monet’s The Magpie, which has now found home in the Musée d’Orsay, once hung in Guerlain workshop – despite public opinion at the time, also found his own decorator in the hands of artist Jean-Michel Frank.

So, the spirit of artistic revelation has since crept its way into the very fabric of Guerlain’s sensorial oeuvre, most patently in the L’Art & La Matière collection, which intentionally pairs perfumers with works of art in hopes of inspiring brand-new olfactive creations. In the past, Rose Barbare was borne out of George Bizet’s opera Carmen; Neroli Outrenoir, a scent-rospective of the works of Pierre Soulages; and Musc Outreblanc, a distillation of Auguste Rodin’s sculptural masterstrokes. And this season, Henri Matisse and, specifically, the painter’s The Thousand and One Nights served as a vivid reference point for what ultimately became Jasmin Bonheur.

While Guerlain waltzes with Matisse, Louis Vuitton, this season, found camaraderie in the polka-dotted madness of Yayoi Kusama. Perfume bottles have long been blank canvases for artistic interpretation, because more than any other beauty issue, fragrance is made to be spritzed, ever so sparingly, and then left gingerly alone to double-duty as fragile decor – or clutter – as much as it’s a thing to be used. And what is art if not a thing to be seen, to be admired, be it Penhaligon’s Portraits’ magnificent animal-head stoppers; Jean Paul Gaultier’s iconoclastic naked torsos that can possibly rival that of David of Michelangelo; Vyrao’s gradient- blend glass coffrets that look almost like aura photography; or Kusama’s Louis Vuitton residency – and before her, Alex Israel; and before him, Frank Gehry?

And still, should the folds of fragrance, not the glass-bottled canvas itself, be used as a medium, it could, quite possibly, be the most unreliable narrator of all.

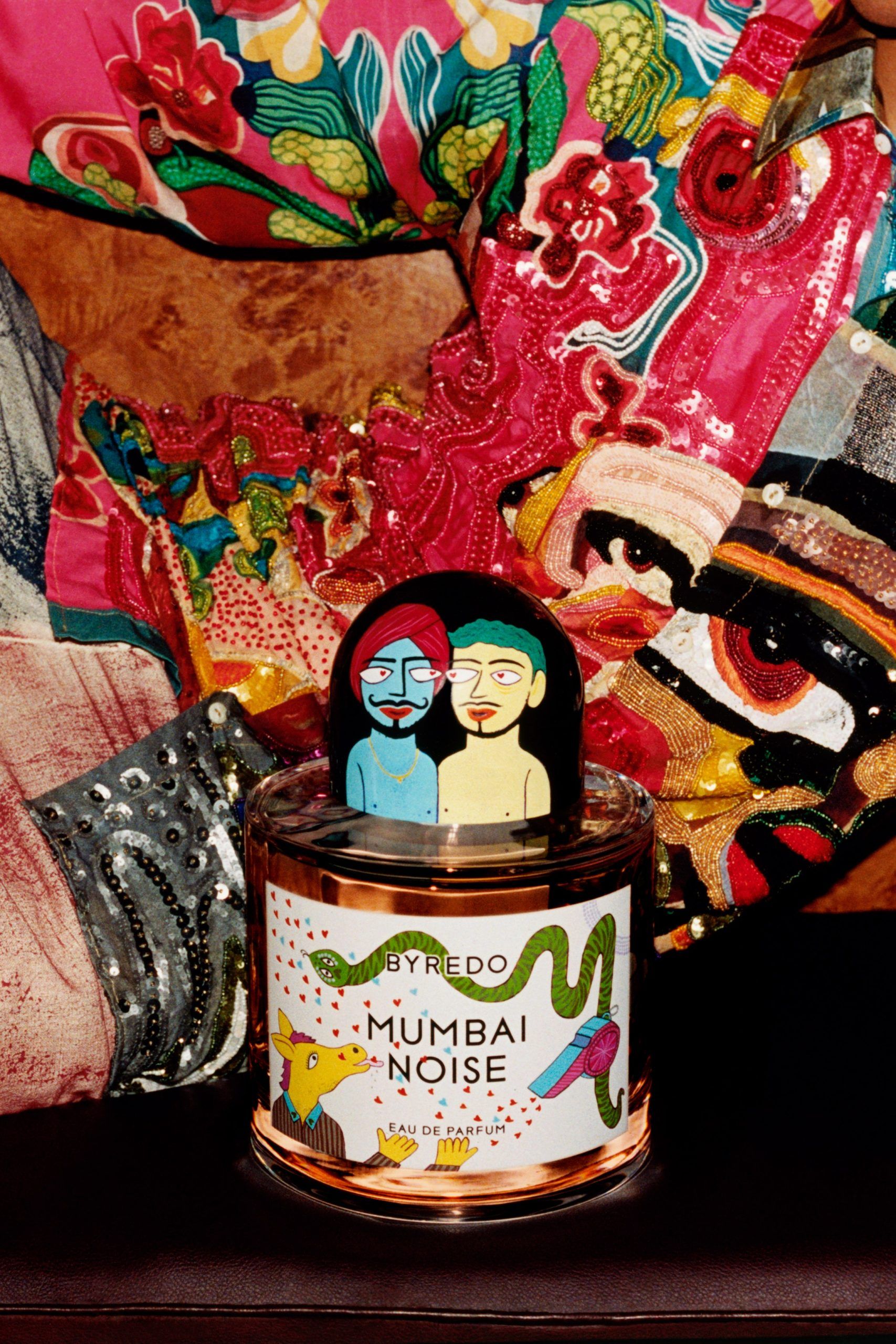

While Byredo’s library of scents has always felt like self-portraiture for founder Ben Gorham – Bal d’Afrique, for example, is a reimagination of his father’s travels through Africa as a young man; and Mumbai Noise, described by Gorham as “intensely personal”, recalls the sensory overload he remembers as so formative to his childhood in India – it would seem remiss not to mention: Gorham trained as a painter but a chance encounter with perfumer Pierre Wulf convinced him to have a change of medium.

And while Gorham draws, typically, from the autobiographical, Stora Skuggan’s co-founders take on narratives that tender towards the extraordinary. “Our perfumes are based on stories on the border between truth and myth,” says the Swedish perfumery’s co-founder Tomas Hempel. “For Fantôme de Maules we assumed the phantom – he or she – really existed. Witnesses talk about a figure who’s two metres tall, so my assumption is the phantom was a man. Silphium is a mythical plant from ancient times. It probably existed too, but one cannot be sure. Our third perfume, Moonmilk, is inspired by a phenomenon that actually exists, but it’s something most people know nothing about. At least I didn’t, until recently.”

The phenomenon the perfumer speaks of was documented by Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner in 1555 of the precipitate that gathers on the surface of limestone that, as it was once fantastically surmised, was a liquid mist created by the rays of the moon. Moonmilk. It’d be notes of black tea, lime and tan leather that would distil the otherworldly marvel into a Stora Skuggan scent.

Then there’s Mistpouffer, that attempts to render into aroma a mystic, sonic boom, still unexplainable by science; Thumbsucker, narrating Ancient Hindu tales of magic potions that illustrate, however incredulously, why babies suck on thumbs; and Azalai, a redolent impression of a lonesome caravan route that once transported salt and gold.

And in between Byredo’s non-fiction and Stora Skuggan’s science-fiction seats, quite comfortably, Folie à Plusieurs’ pastiche of scents directly impressed from works of art, be it music, photography, literature – Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore, apparently, smells of lavender, birch tar and cedarwood – or film.

Not unlike those of unpleasant theme-park 4D screenings, Folie à Plusieurs’ Le Cinéma Olfactif perfumes, a much more sensorially pleasing experience, were created to aromatise specific movie scenes as per perfumer Mark Buxton’s nose and, in collaboration with various Soho Houses, viewings of said films would then be hosted with the scent diffused throughout, using the additive of scent with effects not unlike that of the film’s musical score, or a specific lighting choice, or an editing trick of the eye.

“Typically, you create a product and figure out how to make an experience,” says Kaya Sorhaindo, who founded the brand as an “intermedia perfumery” that acts as a sort of olfactive gallery space. And these experiences, for Folie à Plusieurs, gains traction in ever more sensory collisions; their most recent, a foray into incense paired alongside the eerie, experimentation sounds of Japanese voice artist Hatis Noit, render an entirely sightless performance experienced only through scent and sound.

“We wanted to look for new references, new areas of inspiration and not pull from the same pool as all of the other perfumeries,” Sorhaindo admits. And what is art if not something excitingly new, excitingly collaborative and, possibly, excitingly fragranced? Welcome to the dawn of a new art medium.

Subscribe to our newsletter to get the latest updates.

Thank you for your subscription.